By CURT BROWN Star Tribune of Minneapolis

Published Jun 2, 2003 (This is excerpted from the larger published article.)

In Virginia, Iron Range’s last synagogue in limbo

In Virginia, Minn., “a magnificent jewel of a building” was once the center of a vibrant religious community. Now the region’s last temple stands in limbo, down to two members – and many memories.

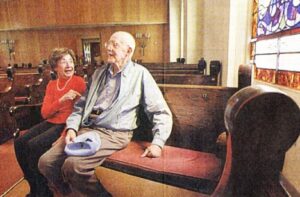

Dr. John Siegel and Dorothy Karon are the last remaining members of B’nai Abraham Synagogue in Virginia, Minn.

VIRGINIA, Minn. (AP) — In the last synagogue on the Iron Range, Dr. John Siegel glances up at the eternal light fixture, a stained-glass swirl of purple and pink. “It’s burned out,” Siegel said with a shrug. “When I was younger, I used to put a ladder on that table up on the bema and climb up to change the bulb.” Back then, there was no problem keeping the electrified symbol of an everlasting oil lamp alight. B’nai Abraham Synagogue was packed with people such as Chaim Siegel, the doctor’ s Lithuanian father, who dabbled in the cattle business and sold ” meat, junk and anything he could to make a dollar.”

In those days, the sound of someone clomping up the stairs on a bad leg probably came from Frieda Schwartz, who had suffered a stroke back in Europe. Her journey from Poland to America had been delayed for several years after World War I broke out the day she was set to sail from Hamburg, Germany.

Joseph Roman, owner of Virginia’ s Rex Theatre, came to the synagogue with his wife, a fierce player of poker and canasta. Then there was Jack Zimmerman, a furniture-shop owner who was Bob Dylan’ s uncle, and the three Russian-born Shanedling brothers, who opened the town’ s first Sears store.

The brothers organized the fund drive to build the handsome red-brick temple with arched, stained-glass windows in 1907. They collected money from women who sold jewelry they had carried from the Old World, and they won a hefty donation from catalog mogul Richard Sears.

Today, membership at B’nai Abraham has dwindled to two: Siegel, who turns 90 this month, and Dorothy Karon, 83, Schwartz’ s granddaughter and the last branch on a family tree that includes ancestors who owned a local oil company and a scrap-metal business.

Services have been infrequent for the past few years, as the Range’ s disappearing Jewish community has been unable to convene the traditional quorum of 10 Jewish men, or minyan, necessary for worship.

The six sacred Torah scrolls, which Jewish rules say must remain in regular use, have been lent to congregations in Duluth, Rochester and Honolulu. Despite its perch on the National Register of Historic Places, the temple owned by the B’nai Abraham Synagogue Society was recently listed among the 10 most endangered structures in the state

” After Dorothy and I are gone, I don’ t know what’ s going to happen, ” Siegel said. ” It will probably be sold.”

So far, they’ve fought off that fate, opposing a sale suggestion from a former member in the real-estate business and overtures from a Lubavitch rabbi in St. Paul. Siegel and Karon don’ t want their temple to disappear. Eveleth’ s synagogue was sold to a carpenter’ s shop and destroyed, Chisholm’ s was demolished and Hibbing’ s was converted into a church.

” This is the last evidence we have of a very vibrant Jewish community on the Range that once included more than 1, 000 people, ” said Marilyn Chiat, a Minneapolis art historian and University of Minnesota expert on religious architecture. ” It’ s really a magnificent jewel of a building.”

Chiat said she has ” talked myself hoarse with those folks” about the temple’ s future. She admires the protective zeal of Siegel and Karon, but would like to see them sell the building to the city of Virginia for $1, so the city could maintain it as a museum of the Range’ s diverse past, make it available for Jewish ceremonies, and possibly feature concerts or historical programs.

” Being protective is all well and good, but it’ s one thing to hang on to a sacred space as close to your chest as you can, ” Chiat said. ” It’ s another thing to recognize that none of us are immortal and it’ s important to save the last evidence of a Jewish presence on the Range.”

Stan Shanedling of Minneapolis, whose grandfather Morris’ name is etched in one of the stained-glass windows, would like to see Twin Cities-area synagogues form some sort of consortium and use the temple as a northern Minnesota retreat for youth groups or special services.

In the meantime, Siegel and Karon pay the heating, electric and lawn-care bills. On a recent Sabbath Saturday morning, they swept up a dead bird and sifted through memories in sunlight tinted pink, purple and teal by the stained-glass windows.

” When I was one week old, I was given my Jewish name — Sprinsa Leah — right here on this bema, ” Karon said, stepping up on the temple’ s prayer platform. ” My grandmother used to head up the stairs because the women weren’t allowed to sit downstairs with the men.”

In the 1940s, Siegel recalled, the temple’ s last full-time rabbi and Hebrew teacher was still on duty and the building’ s basement study hall often served as a kosher banquet hall for ” big affairs, ” such as his son Elliot’ s 1954 bar mitzvah.

” On the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, this place was packed, standing room only, ” said Siegel, who retired 20 years ago. ” Fights used to break out with people arguing that someone stole their seats.”

To forestall fisticuffs, all 31 oak pews, nine in three sections in the main sanctuary and four upstairs, were emblazoned with numbered seats.

So what happened to all the Jews on the Range?

Experts point to many of the same economic forces that devastated towns like Hibbing, Chisholm and Eveleth as the mines closed and their well-paying jobs disappeared.

The hard times combined with social features in the Jewish community to create a mini-Diaspora, sending the sons and daughters of the original immigrants off to Minneapolis, Chicago and other cities to pursue careers.

Unlike in other immigrant communities that tended to be dominated by single men seeking work, Jewish families came to the Range together, bringing high literacy rates and respect for the value of formal schooling. Their children were well-educated in the excellent schools subsidized by the mining companies.

” When Iron Range business got bad and the mines started to close, the merchants on Main Street had less customers, ” Chiat said. ” The schools were outstanding, and the Jews were like many immigrant groups who couldn’t speak English, but valued education, and their sons and daughters became accountants, lawyers and doctors and moved away.”

Anti-Semitism, while prevalent in Minneapolis, was hardly a factor on the Range, Chiat said. A swastika was once painted on the sidewalk in front of the temple and the Ku Klux Klan marched in Virginia in the 1920s.

” But the KKK didn’t like the Finns’ socialism, ” she said. ” In some small towns, Jews tried to stay invisible, but on the Range they built four temples, ran for the school board and were part of such a mixture of minority groups, there was actually very little overt anti-Semitism.”

Now Siegel and Karon are the only two active B’ nai Abraham members left. Siegel yanks a curtain, embroidered with the Hebrew words for the tree of life, unveiling the oaken ark where the Torahs once sat. In one drawer, he finds a silver Kiddush cup engraved in the memory of Roman, the theater owner.

Karon discovers a pair of yads, the sterling silver pointers that are used to follow lines in the Torah because human hands are not supposed to touch the sacred scrolls. From another drawer, Siegel takes a wooden spice box and sniffs the old cinnamon sticks used to celebrate the end of the Sabbath, and blows a ram’ s horn shofar.

In the basement, the kosher dishes are ready for another bar mitzvah feast, one that may never come. Dusty prayer books and prayer shawls are scattered as if their users might stroll through the door and take them up again tomorrow. The names of Chaim Siegel, Frieda Schwartz, Morris Shanedling and Joseph Roman, as well as other long-gone members of the congregation, are displayed on plaques along with the dates of their deaths. When Siegel flips a hidden switch, tiny light bulbs illuminate the names.

Karon points over the bema to two carved lions bracing a Ten Commandments tablet carved in 4 feet of mahogany.

“That’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen,” she said. “If we ever did have to sell this place, I’ m going to get it taken down and brought to my house even if I have to move one of the couches out of my living room. I’m not going to just let anyone have it.”

Even if the eternal light has long since burned out